Sprache

Typ

- Buch (6)

- Wissenschaftlicher Artikel (2)

- Interview (0)

- Video (0)

- Audio (0)

- Veranstaltung (0)

- Autoreninfo (0)

Zugang

Format

Kategorien

Zeitlich

Geographisch

Nutzerkonto

“Poetry must be made by all. Not by one.”

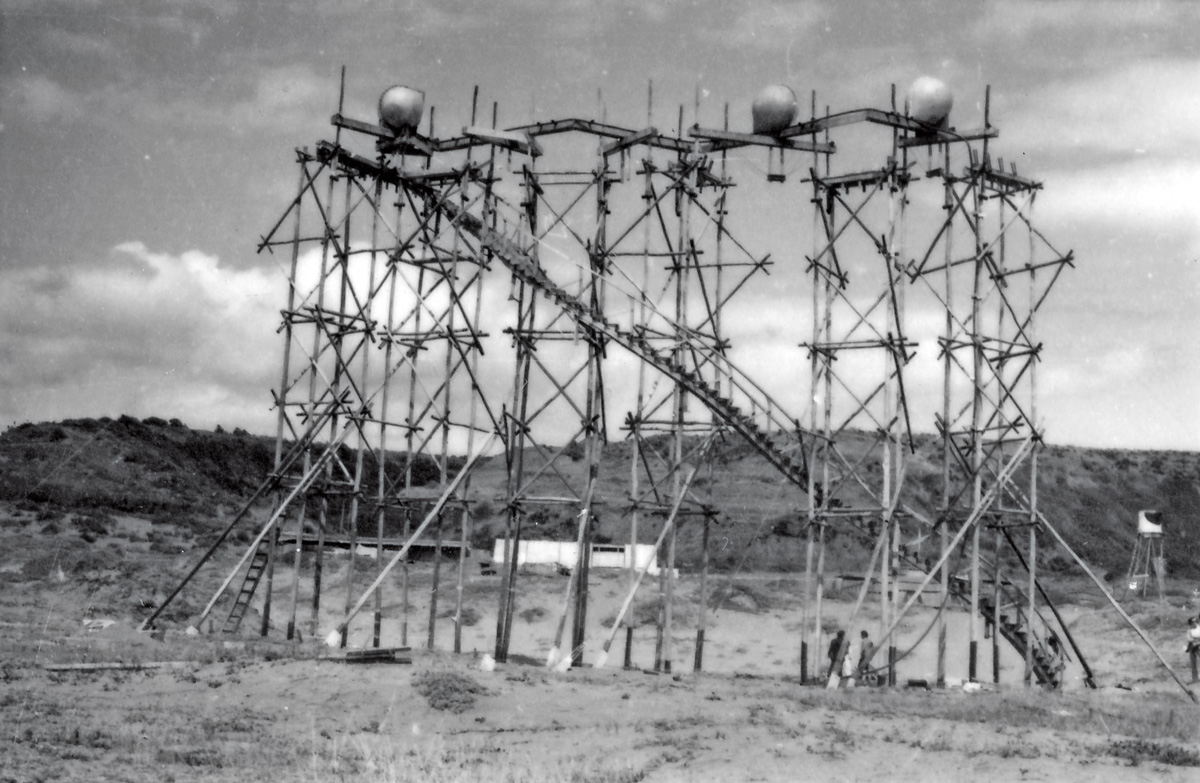

Around thirty kilometers north of Valparaíso, the interdisciplinary open-air laboratory and event campus of the architectural institute of the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso extends along the Pacific coast: the “open city,” Ciudas Abierta, where architecture has been practiced for forty-five years now according to a basic postulate that is as simple as it is conceptual and abstract: the aim is to understand architecture as a variety of poetics; to think of both space and technical practice from the point of view of language. Use is made of a concept of poetry that is always left vague and as open as possible, and in which the human being is seen as central, not as an anthropometrical reference—as with Le Corbusier, for example—but as the bearer of a state of mind. Alberto Cruz, who formed the institute’s early intellectual duo with the Argentinian poet Godofredo Iommi, said at the time that architecture should primarily be conceived as playing with intimacy, in a continual tension between concealment and disclosure, rooted in life and the present. In this sense the spirit of poetry is equivalent to transience: poetic architecture plays with the ephemeral. This only apparently sounds like Buckminster Fuller’s concept of ephemeralization, which is ultimately founded on an idea of efficiency—producing more and more with less and less—that is certainly not central to the tradition of the Ciudad Abierta. It comes more from an idea of precariousness; the emphasis lies on transience. So the buildings, which emerge from an interplay of veiling and unveiling, are variable, precarious, presentist, but not necessarily more efficient. Architectural design, seen in this way, should be understood more as the projection of a present into the future than as the establishment of a future. A state of mind is projected. But the architect of the Ciudad Abierta shouldn’t primarily be seen as a projecting poet, rather as a reader who apprehends the transient, that is present-day life, through language, and proceeds to spatial design from this reading. The project initially takes place through language. Alberto Cruz writes that in order to construct a building an extensive terrain has to be waded through before dealing with the material aspects: the terrain of asking oneself questions. The way through the mire of language is at least as important for the construction of a building as its material conditions or concrete surroundings.

Ciudad Abierta is a vivid example of how buildings aren’t necessarily more solid than trains of though or linguistic constructs. Whatever is built there is built on sand. Half sunk into the dunes, the metal and wooden constructions stand as symbols of transience and mutability in a scenery that exemplarily doubles what can be observed in practically every Chilean city: the city as a patchwork that has to be rebuilt, repaired, rethought after every tsunami. The architectural laboratory of the Ciudad Abierta thus reflects an economy of thinking and feeling that has been formed over the centuries by natural disasters; a way of thinking that is equally influenced by geographical circumstances and the fragile but indestructible spirit of the poetic; a thinking in which destruction doesn’t represent a latent threat but an endogenous, phantom-like presence.

From the perspective of its founders the Ciudad Abierta is constrained by two seas: an open sea—the Pacific—and a closed one—the “inner sea of South America”—an impassable terra incognita traversed by the longest mountain range in the world, extensively covered by thick jungle, and straddled by landscapes of sand, salt, and stone, superlatives of inhospitableness: the world’s driest desert, the largest salt lake, the most similar conditions to Mars. The voyage of discovery across this inner sea, initiated in 1965 under the fantasy name of Amereida, forms the background to the Ciudad Abierta of today. The portmanteau word Amereida, which amalgamates America and Eneida (Aeneid) effectively concentrates the journey’s entire program to the maximum: the aim was to stage a South American Aeneid on the continental sea; a journey like a founding mythology, a large-scale “geopolitical study” that was conceived from the start as a cartographic game of projection and inscription whose route traced the Southern Cross omto the continent. The first stage, from Tierra del Fuego to the Atlantic coast of Venezuela, defined the north-south axis of the constellation. It would initially be only partially covered, up to south-east Bolivia, to Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the designated capital of Amereida, intersection of the constellation’s two axes. The expedition set out from Punta Arenas, the southernmost city of the American mainland, a conglomeration of seemingly Adriatic architectural finery and Chilean corrugated iron, on whose banks the Straits of Magellan has the appearance of a constantly grey estuary. From Punta Arenas the journey would mostly be on poor and rarely asphalted roads, through mud and snow, through the void of the inner sea of Amereida; a wandering with far more obstacles than connections.

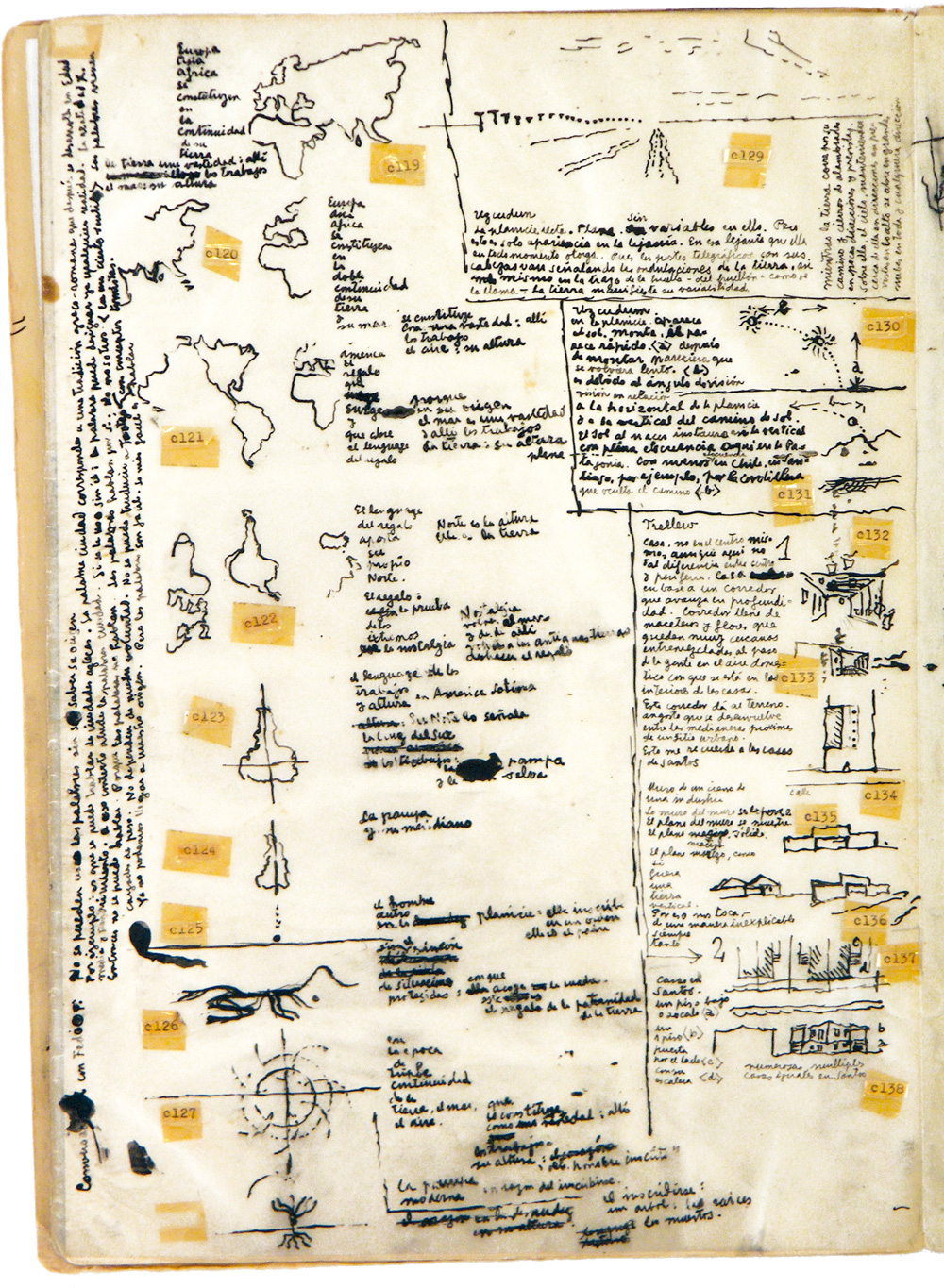

Amereida was an attempted road trip without a road. A voluntary shift into aporia—in the narrow sense of the word, that is the absence of a road. The expedition started in late July 1965, in the depths of the southern-hemisphere winter. From Santiago its participants—ten poets, artists, architects, philosophers, including, as one is inclined to think, three French as observers—were flown via Puerto Montt to Punta Arenas, where the journey’s poetics were negotiated and the approximate route of the imminent “travesía” = sea crossing was fixed. Poetic happenings of all kinds were planned for along the way, and with them the lines and stanzas of a South American founding epic were to emerge.

Writing and voyage began on July 31 in the middle of a heavy snow storm. Ten men in a small—of all things—Chevrolet bus, a brand that since Álvaro de Campos must count as the poet vehicle par excellence. Similarly to Fernando Pessoa’s great modernist, whose nocturnal drive to Sintra in a Chevrolet develops into a writing method, the Amereida expedition’s Chevrolet serves as a poetic tool of writing and exploration. Travel and writing are poetologically merged, road and letters indistinguishable. Differently from Álvaro de Campos, the Amereida journey produces at least two textual outputs: apart from the poem Amereida, in which the journey is put into verse, or rather transcribed, and which appeared two years later, there is also a travel diary, which lay for many years as a forgotten by-product and was only published in 1986. This later publication exhibits the epic side of the poetic scheme. A plot can be comprehended. The here and now of the poetic act is crystalized in the narration. The driving snow of Patagonia. The road disappearing into white. At some point a snow chain breaks. The bus is stranded, at three below zero, beneath one and a half meters of snow. The journey continues after hours of digging and repairing the chain. But not for long. The Chevrolet ship is always running aground in the void of the inland sea. Emergency accommodation has to be found, in the middle of nowhere. The voyagers find shelter with Croatian farmers, or in squalid semi-abandoned hamlets, freezing through the night, doing it the hard way.

Sometimes the diary of the Amereida expedition reads like a Bolaño plot. And as we already know from Bolaño, a bus trip, particularly in a Chevrolet, has to do with nothing other than poetic production. It’s probably a very South American understanding and practice of poetry. A poetry firmly founded in everyday life and surroundings, and that extends far beyond the domain of language, sound, prosody, and print; but above all a poetry that is understood as a collective work, as Godofredo Iommi often liked to recall with his favorite quotation, one and a half sentences penned by Isidore Ducasse, alias Comte de Lautréamont, born in Montevideo in 1846: “Poetry must be made by all. Not by one.” This idea determined the poetic action of the Amereida travelers, who declared all the events of their voyage of discovery to be collective poetry. Alongside readings, performances, and happenings, the poetic inventory of the journey primarily consisted of “phalènes” = moths, as these games including spectators, friends, new traveling acquaintances were called. They took place in villages, small towns, or in the middle of nowhere, with or without an audience, almost never leaving a trace. Verses were written on stones in the landscape, or recited before windmills.

François Fédier occasionally took photographs, but otherwise the poetic ceremonies were translated into the written language—if at all—as epic verse or diary entries; a sketchy form of documentation, as Michel Deguy, one of the French co-travelers, was later to regret. If the expedition had been filmed, he said, it would possibly have been a quite different success. But as it was, in epic verse, close to mythology, the journey was barely communicable, and quickly faded into obscurity in consequence. But on the other hand what it lacked in communication strategy was also a sign of great coherence. The Amereida expedition took Godofredo Iommi’s poetics of ephemerality seriously. For Iommi, whom François Fédier recognized as the perfect example of a poet without an oeuvre, poetry couldn’t be reduced to written documents but had essentially to be understood as a performative interplay with the transient present. Argentinian by birth and Chilean by choice, Iommi was interested in the poetic substance of the moment, which appeared all the more perfect the more fragile its inscription. In this sense dispensing with a comprehensive documentation of the Amereida expedition wasn’t an omission but the consistent realization of a poetic program, for which no more apt symbol can be found than the tire marks of a Chevrolet in the snow-covered landscape of Patagonia.

What counts in this crossing of the South American inland sea is the ceremonial of the here and now: phalènes without spectators and public events in the South American hinterland, at which the Amereida’s finest moments are reported and the South is praised. A certain missionary spirit shines through at times, something prophetic, of which it is difficult to say whether it is merely a vestige of Catholicism or rather the surface phenomenon of a deeply rooted pattern of thought and belief. But it makes no difference, as an unmistakably Catholic haze lies over the inner sea of Amereida, in which the buildings of the Salesian Society rise out of the wasteland like lighthouses. At times the messianic gleam seems to outshine the poetic project. A biblical tone shows through the poetry; the proclamation of the South as the new North echoes like a promise of salvation. Like a religion, Amereida also promises orientation; a realignment of the continent to the South, a reversal of the world view, the radical change of discursively and graphically fixed hierarchies of above and below, lord and master, North and South. “Nuestro Norte es el Sur” = “Our North is the South.” The wild detectives of Amereida took up this slogan, turning the maps upside down, placing South at the top, as the Uruguayan avant-gardist Joaquín Torres García had done before them in his América Invertida. Amereida promised a turn to the Pacific, a turning away from the Atlantic and thus at the same time a cutting of the connection to the North. At some point the Amereidan poets renamed the cardinal points, bade farewell to the nomenclature of the northern hemisphere, and from then on spoke of light, origin, anchor, adventure, which lay westward, on the Pacific.

Even though the Amereidans declared their expedition over on September 13, 1965, without have reached their interim goal of Santa Cruz, this apparent failure was in no way the end of the project, which soon continued, if in an altered form, with the foundation of the Cooperativa Amereida: micro-thinking replaced the macro-vision of the continent of Amereida; the focus was adjusted to city size. The geopoetical study brought about an open city; the cruise became a stationary research facility for the examination of life, study, and work under poetic auspices. Amereida became sedentary. It ensconced itself not far from the small town of Ritoque, a few kilometers from the estuary of the Aconcagua, in the direction of adventure.

The ceremonial opening of the Ciudad Abierta areal in March 1971 took place under the directorship of the three Amereidans Alberto Cruz, Godofredo Iommi, and François Fédier. It bore the unmistakable stamp of their voyage. The phalènes that formed the heart of the ceremony linked back to the journey and carried on the logic of poetic action. Proceeding from the guiding concepts of “abandono y limite” = “abandonment and boundary,” the participants were led blindfold to explore the dunes in an exercise of stumbling perception intended to provide a physical experience of the significance of the liminal. The Ciudad Abierta has continued to explore and displace the boundary between poetry, life, and architecture since then. “Travesías” have also been on the curriculum since 1984, and so every academic year Amereida is re-traveled in a curious mixture of study tour and pilgrimage without a fixed destination. Following the model of the first voyage in 1965, diaries are kept and documentary material is produced. Every journey creates new documents, which meanwhile amount to a considerable archive; an archive of rewriting and overwriting, variants and palimpsests of a permanent founding voyage

.

Photos: Archivo Histórico José Vial Armstrong

Log book: Archivo Alberto Cruz Covarrubias

For over four decades the architecture of the Chilean Ciudad Abierta has been committed to a poetics that anchors artistic creation in life and the present. It’s a project that in some respects recalls Black Mountain College, where the Bauhaus tradition was continued on North American soil into the 1950s. But despite the similarities, if it isn’t worlds that lie between the college in Asheville, North Carolina, and the Chilean school, it’s certainly the equator, and this is anything but insignificant. The Ciudad Abierta isn’t only situated in the southern hemisphere; it’s a think tank of the South, and it was from the very beginning. The degree to which geographical considerations influenced the genesis of the institution was recently shown in the exhibition La invención de un mar (The Invention of a Sea) in Santiago and Valparaíso. It revolved around the history leading up to the Ciudad Abierta: an epic voyage of discovery across a specially invented inland sea. At this year’s documenta, by contrast, the present-day Ciudad Abierta is in the foreground; a present that can scarcely be adequately understood without the think tank’s genealogy, however.

- Fiktion

- Raumtheorie

- Südamerika

- Architekturtheorie

- Architektur

- Poetik

- Gemeinschaft